Yes. The US Navy fought Chinese pirates.

But before I discuss that, if you are interested in board/wargames, then I recommend this game “Queen of Pirates” designed by one of our midshipmen teams who took one of the wargaming courses I sponsored when I was director of the US Naval Academy Museum. It is a historically based board game based on Zheng Yi Sao. At the time the English and French were fighting in the Med, Zheng Yi Sao commanded hundreds of pirate junks.

The name Preble will be familiar to naval historians, sailors and others. That would be Commodore Edward Preble:

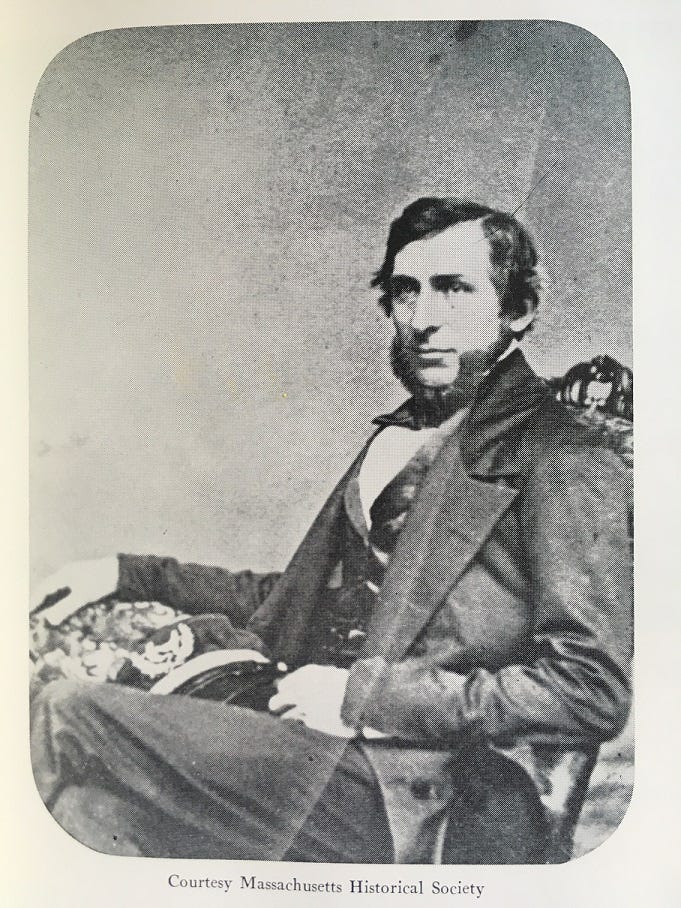

Instead, this story is about his nephew, George Henry Preble, born in 1816 and who entered the navy as a midshipman in 1835:

By 1854 he was a seasoned officer, but as promotions were slow in the 19th century, he served as a lieutenant on Commodore Matthew Perry’s mission to Japan. Perry was one of several officers under the command of Captain Joel Abbot who himself had served during the War of 1812 under Commodore Thomas Macdonough.

(Captain Joel Abbott)

Abbot commanded the USS Macedonian. The ship was built on the keel of the HMS Macedonian, captured by Stephen Decatur and the USS United States in October 1812 and whose flag was also here in Mahan and removed as part of our preservation. The Macedonian was originally built as a frigate but converted to a sloop of war shown here in our collection as well as photographs when she was at the Naval Academy.

By 1854, the United States had seven decades of trade with China. In 1784, the merchant ship Empress of China got underway from New York for Canton, China and signaled a new era of trade for both nations. A year later, the ship Canton left Philadelphia. They were followed by ship after ship and created America’s first millionaires like Elias Hasket Derby of Salem, Massachusetts who owned the Grand Turk.

(Elias Hasket Derby)

The frigate Congress under Captain John Henley arrived in 1819 in China but both local Chinese and American businessmen viewed the warship with suspicion and a threat to the existing order.

(Captain John Henley)

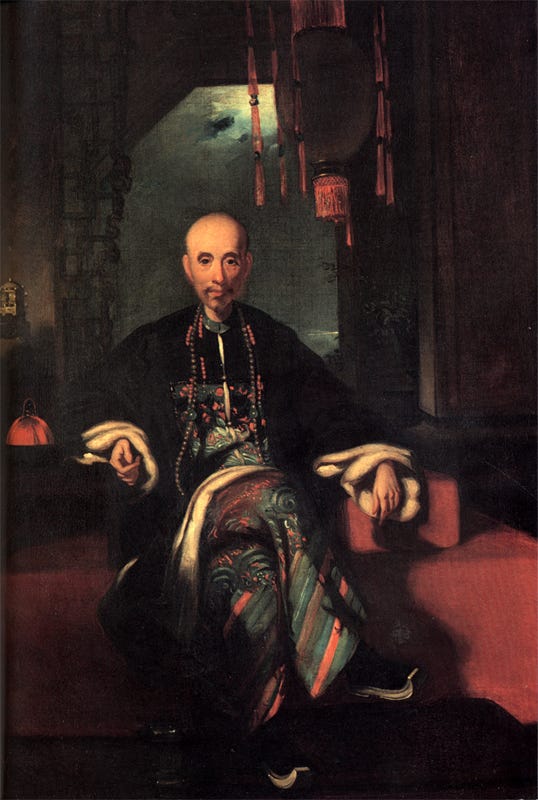

One of the richest men in world until his death in 1843 was a merchant known as Howqua and who was based in Canton, China.

But as we saw with Somali piracy a decade ago, internal disruptions can cause threats at sea and the need for states to respond to maritime piracy.

The Taiping Rebellion began in 1850 – a civil war about which I admittedly have not studied. Suffice it to say that the war eventually took tens of millions of lives. It threatened American and other merchants in Canton and it enabled piracy to rise in the most prosperous coast in Asia.

Commodore Perry arrived in Japan for the second time in February 1854 with a ten-ship fleet that included the Macedonian. The ship remained with the fleet until the signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa in March and then was dispatched to the Chinese coast for surveying duties and maritime security. Perry also ordered that a local steamship be chartered.

That ship was the 137-ton side paddlewheel steamer Queen, owned by an English merchant in Hong Kong at a cost of $750 per month. American steamers had also plied local waters since at least 1830 when the Forbes became the first one to visit Macau. The Chinese called it Fo Shune – fire-ship. Lieutenant George Henry Preble was given command of the ship, forty sailors and fourteen marines. Preble was no stranger to China; he had served there a decade before aboard the USS St. Louis.

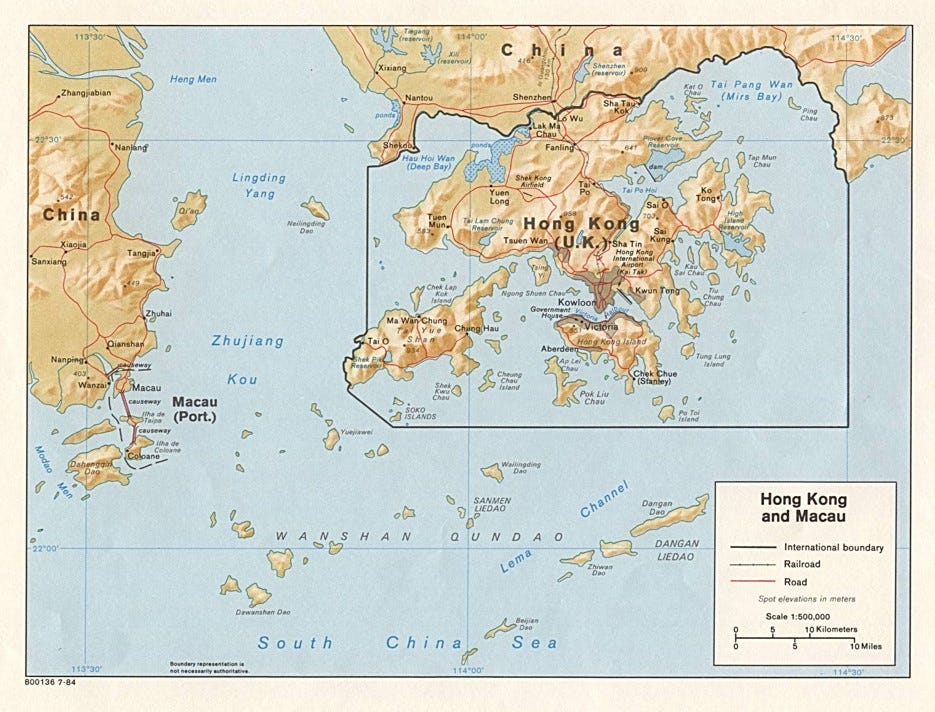

Preble took command on September 1, 1854 with orders to protect American merchants in Canton and patrol the coast between Hong Kong and Macau. Here’s a relatively modern map of the region for this post, probably from the late 20th century before Hong Kohn and Macau were returned to China

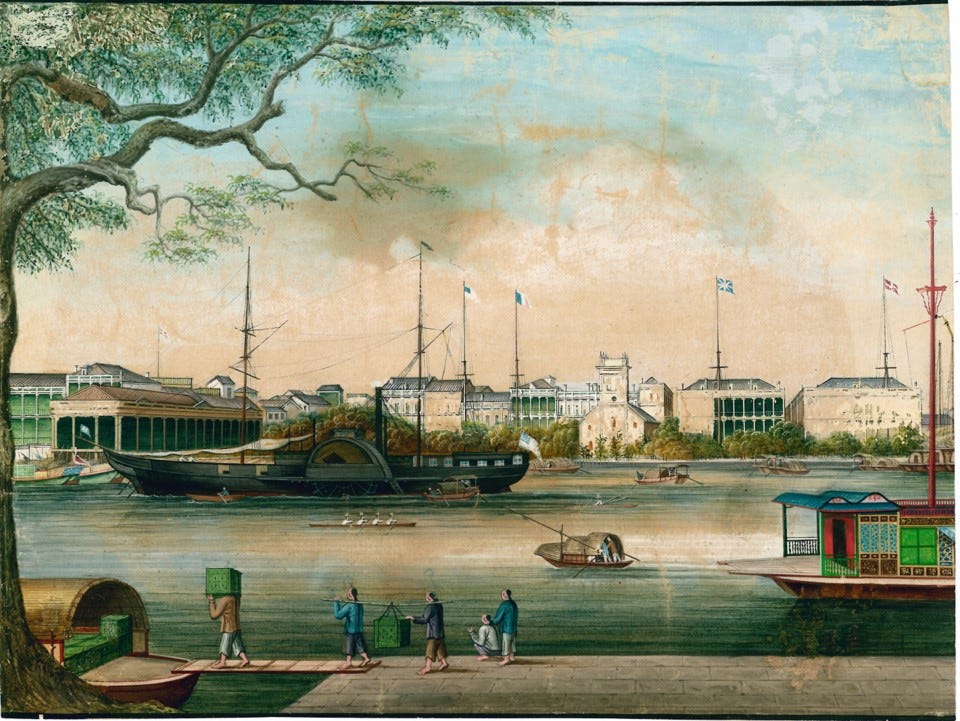

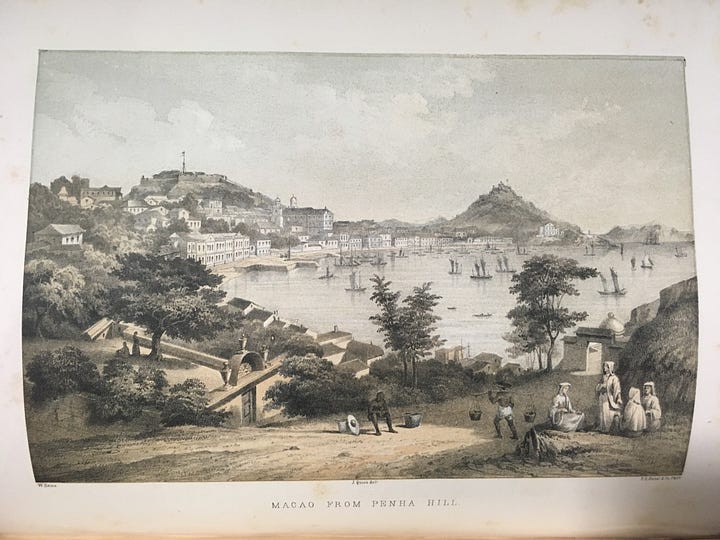

We know what the territories looked like thanks to paintings done in the mid-19th century. The first is of Hong Kong, the second of Macau, and the third of Canton. All are in the collection of the US Naval Academy Museum:

In addition, there are drawings from a period book:

One of Preble’s first impressions while being anchored off Canton was watching the rebel forces attacking the city and captured rebels beheaded. “The rebellion,” he wrote to his wife, “is likely to be as interminable as the War of the Roses.”

The Queen proved to be an able craft with a shallow enough draft to chase local pirates closer to the shore and up the Pearl River. On October 14, word reached Preble that the Caldera – a Chilean flagged merchant ship including two passengers, including a French woman had been taken by pirates. He proceeded to Macau but an indifference to the attack since it wasn’t US-flagged or had US-citizens – much like how we viewed modern Somali piracy in 2005. Preble spent more time writing about breakfasting with the British on blue-winged teal and grilled pigeons.

Less than two weeks later, a new paradigm emerged as Preble, the British, the Portuguese, and the Chinese government decided to work together to attack the pirates. On October 29, Preble used the Queen as a mothership, towing three small boats from the Macedonian and three from the HMS Comus. The landing party attacked the first pirate village and captured three pirate junks. Preble added a boat howitzer and fourteen more sailors and marines including midshipman John Grendy Sproston, an officer later killed during the Civil War.

(John Grendy Sproston)

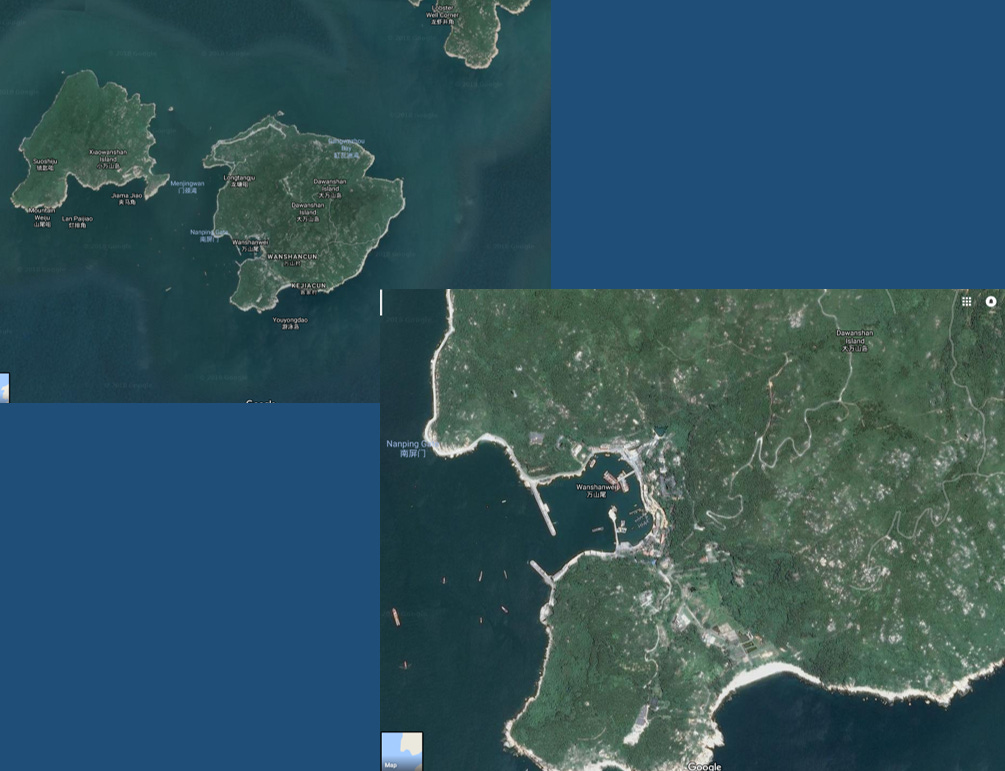

On November 2, the Queen was fired upon by ten Chinese pirate junks in Tylo Bay – off Dawanshan Island - as Preble returned fire.

He pulled away, requested assistance from the Portuguese and re-engaged before heading to Macau to resupply.

On November 3, the Chinese pirates were reinforced by seven more junks; Preble attacked again retreating only when the howitzer carriage was disabled. The joint force landed another party. Preble wrote to his wife that “one of my trophies is a large cotton flag of Lue-Ming-Suy-Ming” – the chief of the sea squadron. His flag said “Takes from the rich and gives to the poor.” He also wrote that the diving line between pirate and rebel is very finely drawn.

The local British commander, Admiral Sir James Stirling of the 52-gun HMS Winchester, had been in the region with three other ships.

(Admiral Sir James Stirling and HMS Winchester)

The anti-piracy flotilla added two more ships with the chartering of local steamships owned by the P&O Company, and the Portuguese ship Amazonia. Stirling organized an expedition to attack the pirates at Kulan Village on Tylo Island seen here today:

Preble immediately volunteered – he wrote to his wife that there wasn’t time to get permission from Captain Abbot and therefore took responsibility.

The small boats landed with a force of nearly 350. Preble wrote that “the whistling of the pirate shot was sharp and neighborly.”

The joint force overran three pirate fortresses, killed up to 50 pirates and destroyed more than fifty pirate junks. The American consul to Hong Kong, James Keenan, fought with a British officer of a flag that Keenan that cut down from the fortress. Preble recounted that the flag was “ornamented with very curious devices, and is undoubtedly the flag of the chief pirate. This and ten other flags taken during the operation were sent to the Department of the Navy.

Following the attack, the flotilla sighted sixty junks under a pirate commander, Pu-Hsing Yu who signaled his allegiance to the Chinese government and would command an imperial fleet. “This unexpected union,” Preble wrote,” brings our expedition to an sudden conclusion.” Preble’s gallantry earned the recognition of Admiral Stirling and the Hong Kong papers.

Six months later, Preble gave up command of the Queen, a fortuitous choice he recalled. Earlier he had been given the opportunity to be the executive officer of the North Pacific Exploring and Surveying Expedition – the Ringgold-Rogers Expedition – but he turned it down for the opportunity of this small command. In 1855, Preble was given command of another chartered steamer – the Confucius – to escort merchant ships near Shanghai where he again fought pirates. “The whole coast…is infested by piratical hordes.” On August third, he again participated in a joint operation with the British against another pirate fleet.

Preble’s actions are not generally taught in naval history classes – they are too comparatively minor incidents and obscured by wars.

Preble later served during the Civil War and retired as a Rear Admiral:

value of naval artifacts to inform sailors and the general public about our history and heritage. Preble understood this. In fact, he wrote a book in 1872 on the history of our national flag and in 1873 was in possession of the Star-Spangled Banner and was the first to photograph it. He had sailcloth sewn to the back to preserve it. There it would remain for forty years until Amelia Fowler worked to preserve it with her team of seamstresses – the year before, she used the same process on the War of 1812 flags. The same flags that have been in Mahan Hall or in the museum’s storage at the Naval Academy for a century.

That includes the Chinese pirate’s flag captured by Preble: