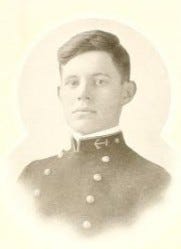

In an institution known for (mostly) producing either warfighters or thinkers, Commander Holloway H. Frost quietly proved he could be both. Born in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, in 1889 and graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1910, Frost belonged to a generation that entered the fleet as the Navy transitioned from a coastal force to a modern blue-water navy. His name is largely unknown today outside of professional military education circles, but his contributions to naval thought raise questions about what he could have offered the Navy during its greatest test: World War II.

Frost began his career during a formative period for American seapower. His name first made a paper in 1909 when he was listed in the top ten of his Academy Class of 1910.

In 1915, he his mentioned in the Washington Evening Star as winning Second honorable mention for an article on tactics, the same year the first prize winner was Lieutenant Commander Dudley Knox. During World War I, he served aboard USS Dolphin, the Secretary of the Navy’s yacht, which was repurposed for patrol duties and sometimes used by Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt. By 1918, as a Lieutenant his second article won the First-Place prize, when the Second Prize winner was Rear Admiral Bradley Fiske. He also served as an aide to Admiral Edwin Anderson during the war.

By 1922, now a lieutenant commander, he commanded the first of his three Clemson-class destroyers, USS Breck.

“During April and May 1924, she helped establish temporary air bases on the Japanese Kurile and Hokkaidō Islands in support of the pioneer, global flight between 9 April and 28 September by the United States Army Air Service.”

His writings, initially through a series of articles on naval strategy, gradually established him as a serious thinker. His name appeared in association with national events like Navy Day in 1926 - speaking engagements included Secretary of the Navy Wilbur and Admiral Gleaves, as well as Lieutenant Commander Frost.

In 1927 as commanding officer of USS Toucey, he met with Charles Lindbergh, both having become book authors with Frost’s co-authored work, “Some Famous Sea Fights,” the first of his four books.

He was sent as an assistant delegate to the 1927 Geneva Naval Conference, formally known as the Conference for the Limitation of Naval Armament. It was convened by the United States with the goal of extending and expanding the principles established by the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, particularly in the areas of limiting naval construction and preventing a renewed naval arms race. The events of that conference exploded in 1929 in newspapers and a Senate investigation because of a former Navy officer turned journalist and political operative, William B. Shearer. Shearer was hired by private American naval and shipbuilding interests to oppose any further naval limitations that might emerge from the Geneva Conference. The scandal damaged the credibility of the arms control movement and raised questions about the influence of private industry on foreign policy. The participating nations adjourned the talks without a treaty or formal resolution. Long-time 20th century journalist Drew Pearson covered the story that included a meeting between Shearer and the delegates - two admirals including Rear Admiral Joseph Reeves, Frost, and Commander Harold Train. Train would rise to the rank of admiral and serve as the commander of the Office of Naval Intelligence, as would his granddaughter, Rear Admiral Elizabeth Train.

Promoted to Commander in 1928, he was assigned as a student at the Army War College in Washington but would then be asked to serve as a faculty member in 1930 as a Commander, the year after his book “We Build a Navy” was published. One newspaper reviewed it just below the new Hemingway book “A Farewell to Arms,” citing Frost’s contention that

A blanket approval of all events of our early history does not distinguish between the excellent, the good and the mediocre. It lowers our standard of measuring ability. It often furnishes a precedent, unconscious perhaps, upon which future commanders may base their decision - with unfortunate results. It gives us an idea of our own invincibility - which, though, perhaps stimulating in small does, may prove fatal in large. Certain our record of these years is splendid enough to stand squarely upon its own merits, without being bolstered up, as an Englishman amusingly said, by ‘American gasconade.’

By 1931, newspapers refer to him as “a well-known naval officer,” and his professional network included future leaders like William S. Pye and Arthur Hepburn.

In response to a book by a Japanese officer about the state of the US Navy, Frost took to the newspapers to refute the book’s contentions.

In 1932, the Washington Post published a four-part series by Frost comparing the US and Japanese fleets.

He then served as Fleet Operations Officer under Admiral David Sellers, then Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet. During Fleet Problem XV in the Panama Canal Zone, he observed firsthand the evolution of fleet doctrine.

In 1934 he detached and took on a second faculty role at the Command and Staff College at Fort Leavenworth. Frost had significant operational experience as a ship commanding officer, had participated in key diplomatic negotiations, was tied to some of the best minds of the fleet and had served under significant flag officers, and he was publishing in history, strategy, and operations. Frost’s career suggests that he would have been one of the extraordinary flag officers the US produced in time for World War 2. Frost may have risen to command a cruiser division or taken a lead staff billet in Nimitz’s headquarters. His peers—officers like Pye, Kincaid, and Hepburn—assumed those responsibilities. Frost was part of that cohort and arguably better equipped than most to bridge the gaps between war college theory and war zone execution. In particular, his emphasis on signal clarity, doctrinal flexibility, and joint planning would have matched the operational demands faced by Allied naval leadership during the Guadalcanal and Central Pacific campaigns.

However, Frost died unexpectedly in 1935 at age 45 from meningitis, just months before the publication of his most significant work, The Battle of Jutland: A Tactical Analysis. The book was published posthumously and reviewed positively by naval scholars, including Professor Allan Westcott of the Naval Academy, who praised its balance of critical insight and professional detachment. It was not polemical, and it did not argue a cause. It was, as Westcott noted, the product of an officer who understood the operational and human factors of naval warfare in equal measure. Jutland wasn’t just a book topic - Frost had had two decades of study to prepare for it. From “The U.S. Navy Won the Battle of Jutland,” by David Kohnen, Nicholas Jellicoe and Nathaniel Sims in the Naval War College Review:

Given the political stakes involved, USN studies of Jutland had significant strategic ramifications for the future of American naval policy. Following Sims’s lead, the faculty and students at the Naval War College took great interest in the battle. Sims pooled his information with that of his Naval Academy classmate Captain Albert P. Niblack, who was completing studies at the College. Niblack shared the information Sims supplied with Lieutenant Commander Harry E. Yarnell and Lieutenant Holloway H. Frost, among others. Using the Sims material as a basis, Niblack, Yarnell, and Frost amassed additional information from other sources.57 They then conducted a war game to replicate the battle of Jutland in September 1916.

One newspaper lamented that in time Frost might have stood second to Mahan in his intellectual impact to the Navy.

Frost’s legacy is not one of what he achieved in combat, but in how he prepared the Navy to think more clearly about combat. His works were incorporated into the curriculum at the Naval War College and read by officers who would later lead in the Pacific. His was a different kind of influence - quiet, persistent, and professional. Though this piece does not summarize his articles, they are worth exploring - and he did so out of professional development, not out of a self-serving manner, such as with one navy officer who wrote to me in 2021 that what he really wanted a book to add to his CV even if it meant “using” the publisher.

The U.S. Navy often venerates command at sea, but it sometimes forgets the real intellectual foundations that make successful command and successful operations possible. Frost was part of the generation that believed professional military education, strategic reflection, and doctrinal debate were not distractions from readiness, but essential to it. His death in 1935 removed from the Navy one of its clearest minds at a time when such minds were most needed. We can only hope that we have a few Frosts today who have a broader and more beneficial goal than just their own personal career.

Thank you for bringing Frost to our attention. The contributions made by officers like him need to be recognized. Large organizations benefit from people like this in innumerable ways, but the men who start balls rolling are soon forgotten.

Thanks for the great article, I may have to see about downloading this for my ipad to read during an upcoming trip! https://archive.org/details/battleofjutland0000fros/page/n5/mode/2up