The 1850s, like the 1830s, are an underappreciated period of US naval history, as are most periods between conflicts. But the 1850s spawned advances in technologies, the abolition of flogging led by the first Jewish-American Commodore Uriah Levy, and in one annual report to Congress in 1852, the Secretary of the Navy announced preparations for not one or two naval expeditions but five.

The best known of these was that of Commodore Matthew Perry’s mission to Japan to open it to trade, serve as a coaling station, and assist with any stranded sailors from wrecks along the coast. A second was the North Pacific Expedition under Lieutenant John Rogers of the famed Rogers clan serving the navy for more than a century. A third was a hybrid expedition to West Africa in partnership with the Pennsylvania Colonization Society, part of the broader American Colonization Society to establish settlements for freed African Americans. This included Liberia, whose capital of Monrovia is the only one in the world named after a US President. Another was the second Grinnell Expedition led by Dr. Elisha Kent Kane which was part of the international search for Sir John Franklin’s lost Arctic expedition. Although the US Navy did not officially sponsor the expedition, Navy personnel were assigned to it. Lastly, there was the expedition to South America to explore and survey the interior waterways Plata, Paran, and Paraguay.

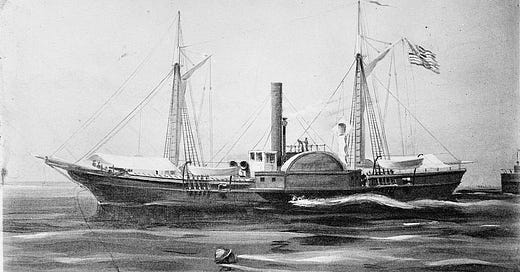

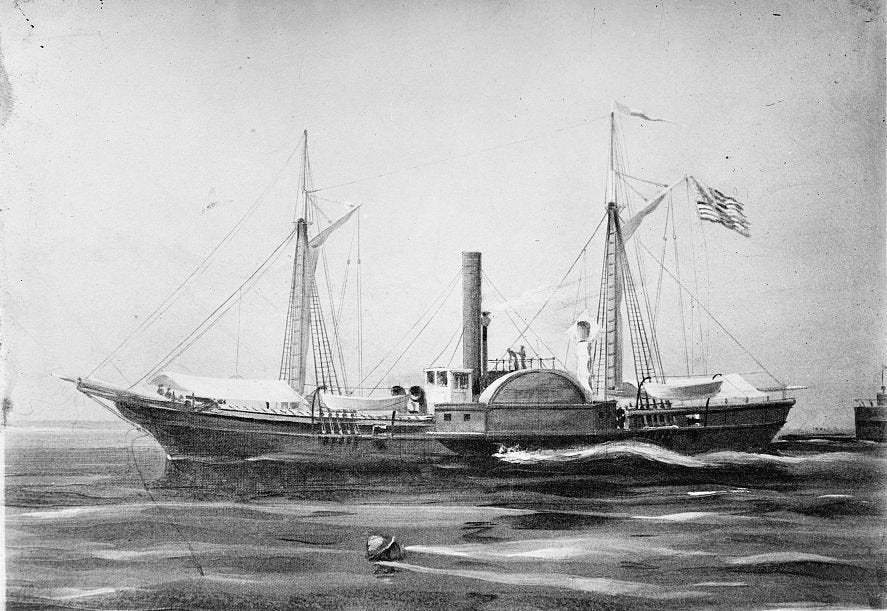

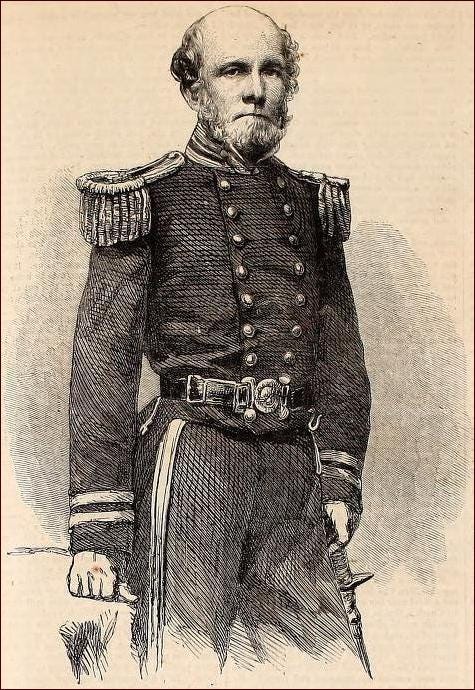

The ship for this mission was the sidewheel steamer Water Witch, a 464-ton, 160-foot long vessel with about sixty crew. In command would be Lieutenant Thomas Page. Like many during this era of slow promotions due to few retirements and billets, Page was in his forties with more than twenty years in the Navy. Another officer on the ship was Daniel Ammen who would later as an admiral design and develop the Katahdin – a ram ship – in the 1890s.

Before her formal commissioning, Water-Witch was at the Washington Navy Yard preparing for a three year mission. On December 23, 1852, she could be seen raising steam to test her engine while remaining on the wharf, the engine and plan that was based on the earlier USS Princeton. On the 30th, she got underway for a test run on the Potomoc River making Fort Washington in an hour and five minutes before making it back in 55 minutes. She was deemed the fastest ship in the navy. In another comparison to the ill-fated Princeton whose cruise on the Potomac testing guns resulted in an explosion that killed two cabinet members (including the Secretary of the Navy) and nearly the president, newspapers reported several dignitaries aboard Water Witch. One paper noted that Secretary of the Navy John Kennedy and Commodore William Shubrick were aboard, while others noted that it was President Millard Fillmore and several cabinet members in the final weeks and months of the administration. If Fillmore’s cabinet were onboard Water-Witch, Secretary of State Edward Everett would have been there; Everett would later be the featured speaker at a battlefield memorial during the Civil War in which he would talk for two hours; he was followed up by a speech of only 272 words delivered by President Lincoln.

On January 16, the ship was in Baltimore provisioning for the lengthy journey and made another port visit in Norfolk. It departed on February 10 to Demerara (in modern Guyana) to bring on coal, the first US Navy ship to visit that port in 35 years. Water-Witch arrived in Rio de Janeiro on April 23 where Page would write to the Secretary of Legation there:

Sir: The expedition on which the Water Witch has been ordered by the President of the United States, having purely for its object the advancement of commerce and promotion of science, objects interesting to all civilized nations, but more especially so to those on whose borders, or into whose territories its operations may extend, I wish, through the legation of the United States, to call the attention of the Brazilian government to this expedition, with the hope that through its enlightened policy it may be disposed to forward the work with which I am entrusted, whensoever its operations may border upon, or extend into the territory of Brazil. Facilities might be afforded and difficulties removed by the simple act of approval and commendation on the part of Brazil, of which her frontier and inland posts could be notified in advance of the expedition. You are too well aware of the good likely to result from the work we have in hand to require any argument from me. I therefore leave the matter in your hands, with the hope that your efforts to advance the aim and object I have in view may succeed to our entire satisfaction.

For most of 1854, Water-Witch wound its way through the rivers of South America. In his annual report, Secretary of the Navy James Dobbins wrote that “Water-Witch is still actively engaged in surveying the Uruguay and Parana Rivers.” A few weeks later in South America, Page would write to Washington that everywhere the ship and crew met “a civilized and kind population.”

And that’s when things went wrong…

In the 1855 annual report, the Secretary of the Navy summarized the events of February 1 as this:

Misunderstandings of a very serious nature, involving a painful collision, having occurred between our Consul and officers of the Water Witch and the President of the Republic of Paraguay, it was deemed expedient by Commander T.J. Page, commanding that steamer, on special service, to discontinue for the present the completion of the survey of the river Parana in which considerable progress had been made…

In less diplomatic words, Paraguayan forces fired on Water-Witch killing the quartermaster and injuring others.

(approximate location of incident)

General Incesloa Robles advised the Paraguayan President that Water-Witch attempted to ascend a restricted canal and that he dispatched an officer to present a decree forbidding passage. The Water Witch's commander dismissed the decree and continued its course, ignoring warnings. In response, Robles reported, the fort fired three unshotted warning shots, which were met with mockery from the steamer’s crew. As the vessel advanced, the commandant ordered it to anchor three times, but these warnings were also ignored. Finally, a shot was fired across the bow as a final deterrent. A skirmish ensued, with the Water Witch and the fort exchanging fire. The fort discharged twelve rounds, striking the steamer’s side and stern ten times, causing significant damage—destroying lifeboats, crippling a paddle wheel, and likely affecting machinery. Paraguayan gunners maintained accuracy, while the Water Witch’s fire proved ineffective, failing to inflict casualties or breach the fort’s walls. With its crew seeking cover and one paddle wheel disabled, the Water Witch drifted back with the current, effectively retreating. The report concludes that Paraguay successfully upheld its territorial sovereignty, demonstrating its military capability while avoiding unnecessary casualties.

Captain Page’s report describes the Paraguayan attack on the Water Witch as unprovoked, unjustified, and dishonorable while the vessel was conducting a peaceful mission under U.S. orders. He recounts that on January 1st, Lieutenant Jeffers, commanding the Water Witch, attempted to ascend the Paraná River, which forms a common boundary between Corrientes (Argentina) and Paraguay. Despite having official permission from the Argentine Confederation and Corrientes Province, the vessel was unexpectedly fired upon from a Paraguayan fort.

(Thomas Page)

The Water Witch was navigating Argentine waters when it attempted to use a channel closer to the Corrientes side. However, the vessel ran aground, making it clear it was not engaging in hostile action. Despite this, Paraguayan forces opened fire, hitting the ship ten times, though not critically. The attack resulted in the death of Quartermaster Samuel Chaney, who succumbed to his wounds within two hours. Several crew members sustained minor injuries from splinters but were able to continue their duties.

Page expressed outrage at Paraguay’s unjustified aggression, arguing that no prior warning had been given, and Paraguay had no legitimate authority to deny passage. The Argentine government had even encouraged the mission, believing the river to be navigable for greater distances, and had provided official documentation ensuring U.S. rights to navigate up to Corrientes' territorial limit. Page insists Paraguay had no legal claim to restrict navigation in this area and deems the attack an act of barbarity, outside the norms of civilized diplomacy.

He fully supported Lieutenant Jeffers’ actions, commending his composure during the attack, and hoped the U.S. government will approve of his response. Page reported that the vessel, though damaged, remained operational and that repairs are easily manageable. Lieutenant Jeffers also provided a report to Page.

The accounts of the Water Witch incident provided by the Paraguayan general and Lieutenant Jeffers diverge significantly, particularly regarding the sequence of events and the motivations behind each side’s actions. One of the most glaring discrepancies concerns the issue of warnings. The Paraguayan general insists that an officer was dispatched to formally warn the Water Witch of the passage restrictions, presenting a written decree that prohibited its advance. According to this version, the American commander not only disregarded the order but did so with open contempt, throwing the decree aside. Jeffers, however, presented a different account. He acknowledged that a Paraguayan canoe approached his vessel and that a man attempted to hand him a Spanish-language document, but he stated that he refused to accept it simply because he could not read it. Nowhere did he indicate that the Paraguayans made any effort to ensure he understood its contents or that he was given a clear verbal warning.

Similarly, the two sides offered conflicting descriptions of how hostilities commenced. The Paraguayan report portrayed their forces as measured and restrained, claiming that they fired three warning shots that were intentionally misdirected before discharging a single live round across the Water Witch’s bow. By contrast, Jeffers insisted that after the initial hails from the fort, two blank shots were fired in rapid succession, immediately followed by a live round that struck the ship. Crucially, he asserts that this first Paraguayan shot did not merely serve as a warning but caused serious damage, destroying the vessel’s wheel and mortally wounding Quartermaster Samuel Chaney.

Another point of contention is whether the Americans responded to the Paraguayans with mockery and defiance. The Paraguayan general described the Water Witch’s crew as dismissive and disrespectful, laughing at the warnings and advancing in blatant disregard of Paraguayan sovereignty. Jeffers made no mention of such behavior, instead presenting his crew as disciplined and focused on their mission. Rather than ignoring commands out of arrogance, he suggested that his ship was simply engaged in the necessary navigational maneuvers when it was unexpectedly attacked.

Despite these differences in perspective, both accounts agree that the Water Witch sustained significant damage. The Paraguayan report emphasized the effectiveness of its artillery, noting multiple direct hits that shattered parts of the ship, including boats on deck and one of the paddle wheels. Jeffers did not dispute that his ship was struck, but he focused more on the operational consequences. He described how the loss of the wheel severely hampered navigation, creating a critical vulnerability in the face of a strong current. For him, the most pressing concern was not just the structural damage but the increasing difficulty of maintaining control over the vessel.

These competing narratives extend to the broader interpretation of the battle’s outcome. The Paraguayan general cast the event as a decisive victory, arguing that their battery successfully repelled the Water Witch, which was left at their mercy before retreating. Jeffers, however, presented his withdrawal as a calculated necessity rather than a forced retreat. He emphasizes that the shallowness of the river and the overwhelming strength of Paraguayan reinforcements—including the war steamer Taquari—made further engagement an unacceptable risk. In his telling, the decision to retreat was not an admission of defeat but a prudent maneuver to prevent the loss of his ship.

Lastly, the two accounts differ in their assessment of Paraguayan casualties. The general claimed that the Paraguayan fort suffered no meaningful losses, stating that all but one of the American shots failed to strike their intended target. Jeffers, however, argued that his forces inflicted at least some damage, noting that one Paraguayan gun was dismounted and that several well-placed shrapnel rounds likely caused injuries, even if he acknowledged that overall losses were probably low.

Taken together, these discrepancies reveal two fundamentally different interpretations of the incident. The Paraguayan account paints the Water Witch as an arrogant intruder that ignored sovereign commands and suffered a humiliating defeat. Jeffers, in contrast, portrays himself as the commander of a lawful mission that was unjustly attacked, responding with professionalism and restraint while ensuring the survival of his vessel.

A month later, as reports began to trickle into the media, Page himself wrote to take one newspaper judgment to task.

Mr. Editor: …in the article alluded to, touching the glorious attack made by the fort at Itapiru upon the Water Witch, there are exclusive rights assumed for the government of Paraguay, which, it appears to my humble judgment, are not sanctioned by the laws of nations…will you take one step further, and inform your readers had you been in the situation of President Lopez would you have issued such orders to the commandant of Itapiru?

Tensions between the two countries simmered. The United States demanded reparations through it would be three more years before Congress passed a resolution in June 1858 authorizing the President (now James Buchanan) to adopt “such measures and use such force as in his judgment may be necessary and advisable in the event of a refusal of just satisfaction by the Government of Paraguay.”

It would be another three years before Congress would ultimately pass a resolution authorizing the President (now James Buchanan) to make reparation for the firing in the Water Witch, as that ship began its return journey to the region to join the remainder of the US squadron off South America. But reparations were made and the matter was settled.

Still, there are many lessons from this one incident.

- Any ship on any deployment runs a risk that some incident can quickly escalate and that is why they tell us to always be prepared and aware.

- Second, while we may not always want or recognized it, there are almost always two (or more) sides of a story.

- Third, the first news accounts are usually wrong. Wait until facts emerge before making judgments.

What became of Page and Water-Witch? In April 1861, both joined the Confederacy. Until it was demolished in 2019, the National Civil War Museum in Columbus, Georgia had a full-scale replica of the ship.

The Navy sent a small ship up a South American river, but didn’t make sure that anyone onboard spoke Spanish. So much for proper prior planning.

Great history. Thanks.