“It's cold this morning, Captain.”

“Cold. And hard.”

- The Hunt for Red October

It’s January. It’s cold outside.

The word cold is imprecise, dependent as it is on the person using it. I and those friends, schoolmates, and neighbors I grew up with in Maine didn’t give it much thought. It was just another aspect of another season that we were accustomed to in the days of pre-dawn hockey practice on outside rinks and evening 5-mile runs in nothing but a simple 1970s-era jogging suit and wool cap. If our bodies required it, we just added another layer - even in the house. My mother, a child of the Great Depression, kept the thermostat at 58 degrees in the winter (something visitors including her constituents noted) because of the cost of heating oil for a large old home. If we ever thought of asking her to turn it up, the answer would always be the same - “put on a sweater.”

Nearly a quarter-century ago, I had six-month orders to a base in the middle of England, no mountains or hills nearby, just the flat plains that allowed the wind to enhance the cold temperatures. I had taken with me a standard seabag of uniforms - service dress blues, summer whites, and khakis with an Eisenhower jacket. I was told that when I got to the base that I’d be issued winter uniforms, the old woodland Battle Dress Uniform. Note: when the military tells you that they will provide you with something, don’t believe them. Such was the case when I prepared for Guantanamo Bay, which rarely experiences anything less than 90 degrees but was issued winter gear along with summer gear, or when my IS1 and I were told we were going to Iraq and when I asked about in-country transportation was told, “don’t worry, it’ll be there when you arrive.”

I asked our DIA overlords, “so where and what are we going to be driving to go to the places you want us to and how can I confirm this?”

The answer: “just get something, any vehicle you see.”

Me: “So if we’re going to buy a local vehicle, are you giving us money for it?”

Them: “Just take whatever you find.”

Me: “You mean steal a local vehicle? Seriously? That’s how you want us to do this?”

Them: “Get what you need. Next issue…”

When I arrived in England, there was no winter gear immediately available. I was told they’d get some more in a few weeks, in February. Walking the base in short-sleeve khakis, a Garrison cap, and a non-insulated Eisenhower jacket in the middle of winter wasn’t optimal and after a week even I found myself complaining about the cold with a couple of other JOs from warmer parts of the country. That was when I made my daily stop at lunch in the post office.

I had only published one history article in a quarterly so I can’t call myself a historian at that point but I had a life-long interest. Consequently, I took notice of the bulletin board where the unofficial base historian posted everyday a “this day in the history of the base,” mostly focused on World War 2 when it had been one of the many airfields that dotted the English countryside with B-17 bombers. Every day I read the summaries - the number that went out, the many lost each mission, and stories from them. It was cold each January of the war. I wasn’t at war. And no one was shooting at me trying to bring my plane down. That was the day I stopped talking about the cold and thought about my dad.

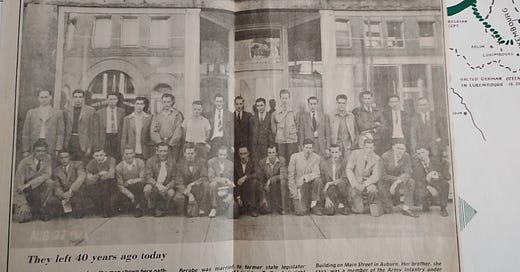

Dad was 18 in 1944 and missed the last couple of months of high school. Along with many in his class, he was drafted and soon after off to training and the war in Europe.

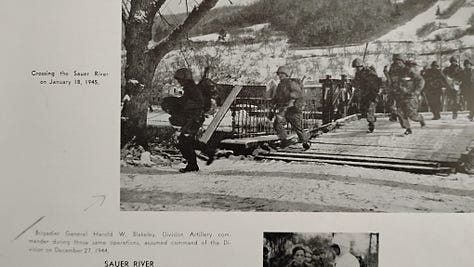

He was in the Army, a private and, according to his discharge documents, his military occupation was “Scout 761.” His uniform, which I could never dispose of, still has his Combat Infantry Badge, the “A” patch on side for the Third Army, and on the other the Ivy patch of the 4th Infantry Division, along with the decorations except for his Bronze Star which came later.

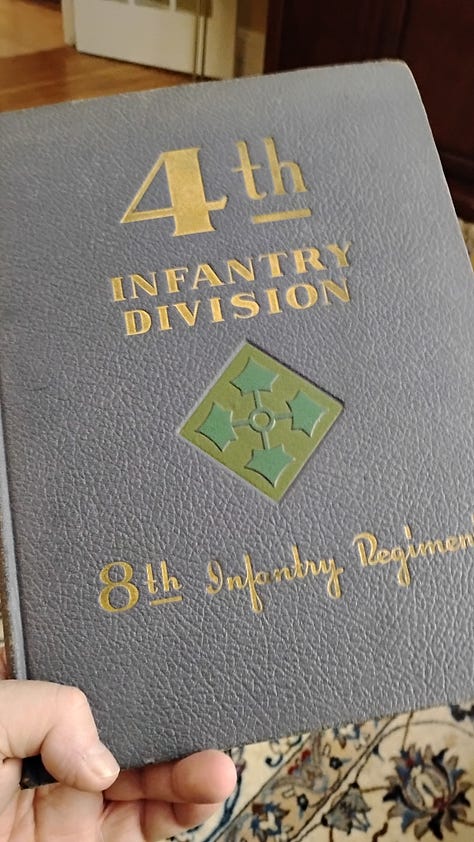

Each January, as I have for more than twenty years, I pull out of my personal library his Regiment book - an account of his unit’s highlights and history of its service during the war. He arrived on January 6, right in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge, Nazi Germany’s last gasp to repel the Allies. He had a skill that many others from his town had - he spoke French like a native since my grandparents had emigrated from Quebec and only spoke the language in the house. Although he died when I was a kid, a few stories or letters from relatives filtered down through the years and the advantage it gave him to serve as an interpreter in France for his platoon. But like most of his generation and war, few soldiers ever discussed their experiences.

Plenty has been written about the weather during the Battle. The oral histories have passed down to us the conditions experienced by one soldier: “Our feet were half-frozen all the time. We never had any place to sleep other than laying in the snow with our backpack and a rifle.''

Dad’s book for the 8th Infantry Regiment is marked up with images he recognized from his time there.

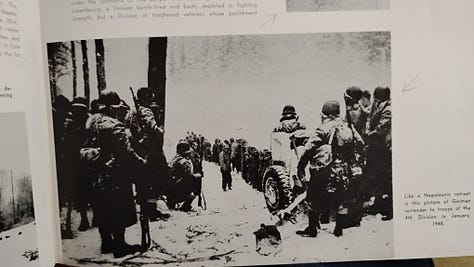

This was especially true of the list of the unit’s command posts during his own service and the changing nature of the battle:

December 27-January 16: Senningen, Luxembourg

January 17-22: Heffingen, Luxembourg

January 22-28: Fels, Luxembourg

January 28: Trione, Belgium

January 28-February 2: Lommersweiler, Belgium

February 2-4: Durler, Belgium

February 4-7: Arnelscheid, Belgium

February 7-March 4: Prum, Germany

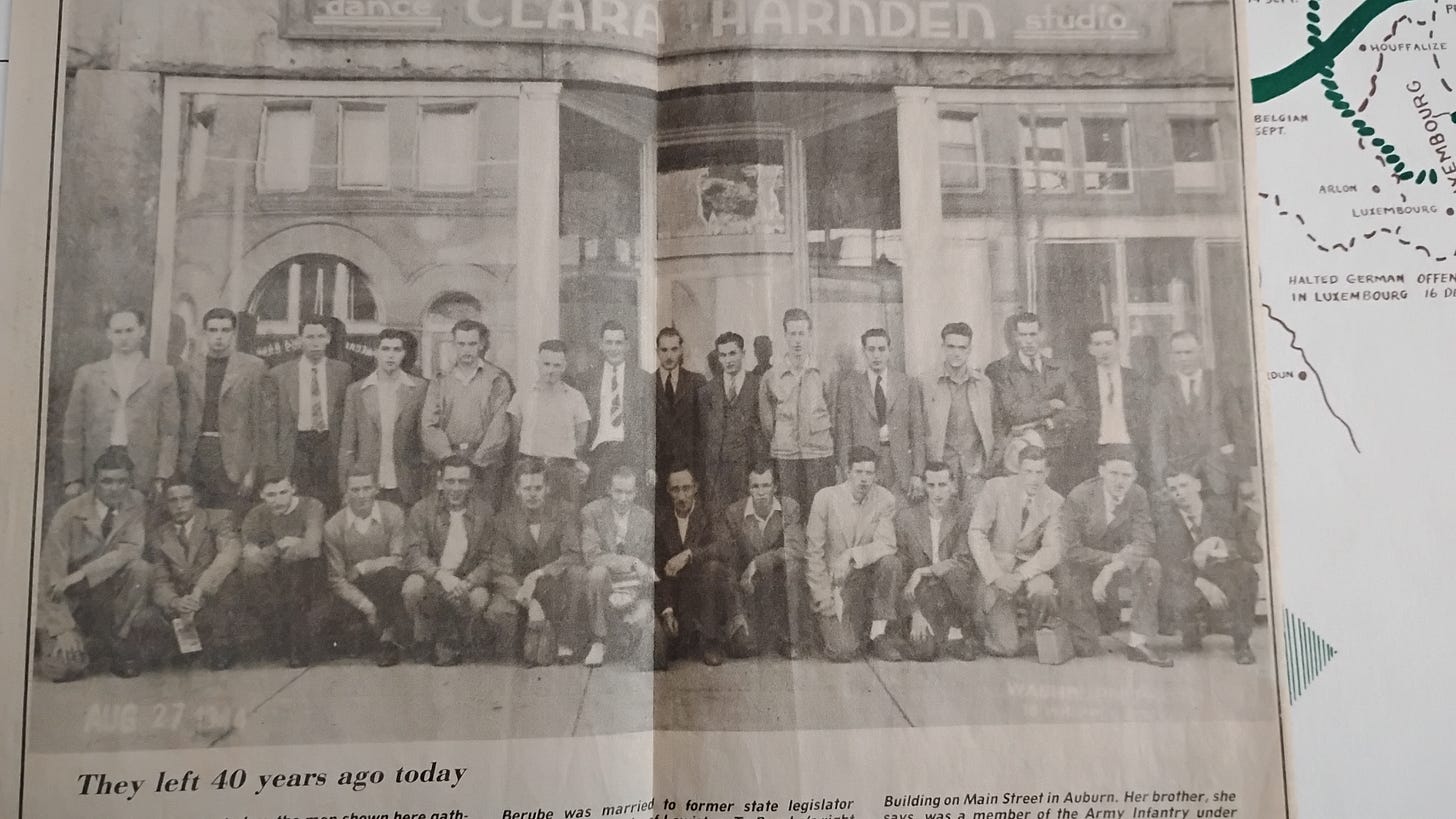

That’s where he marked off the end, though HQ would change nearly every two days for another two months. That’s because it’s when the cold finally got to my dad. The severity of the frostbite required some surgery. He’d spend time recovering in the immediacy of the battle at a field hospital that had been set up at a chateau in Luxembourg. He eventually was sent back to an Army hospital in North Carolina and eventually recuperated, being discharged with his Certificate of Disability. The cold had accounted for nearly half as many of the 8th Infantry Regiment’s non-battle casualties (12,430) as battle casualties (21,849) through the war from D-Day to VE-Day. That was just one regiment. One estimate suggests more than there were between 40,000 and 50,000 cases of cold injuries during the winter of 1944-45 in the European Theater.

The cold never bothered my father. A decade after the war he took a job working in northern Quebec at a mining company. All the photos of those years of him amid the glacial snowfields are of him smiling.

Maybe that’s why I now take the cold with a grain of salt because conditions can always be worse. “Adapt and overcome,” as one of my late-former students used to say.

Now with just another trip to finish my research on his regiment and platoon, I intend to trace his footsteps in those places he fought both the Germans and the weather. But it would have been something nice to do with him. Especially in the cold.