About a year ago I was having one of my regular lunches with VADM Bob Monroe, who unfortunately passed in June. Bob had been the Director of the Defense Nuclear Agency and Director, Navy Research, Development, Test and Evaluation in his last two assignments under Presidents Carter and Reagan. As a historian, I learned a lot about Cold War operations and decisions from him; as a person, I was enriched by knowing him. He was a consummate gentleman and mentor. Every time I met with him, I learned something, sometimes by accident. As an officer, I never served under him, but I wish I had.

He graduated first in his Naval Academy class of 1950 and became a Surface Warfare Officer. I asked him what compelled him to select his first ship. (Ship selection night at the Academy means that midshipmen select their ship based on class ranking.)

Monroe: Back then we didn’t select our ship. It was done by lottery because they didn’t trust us if we graduated near the top [he takes a sip of wine.]

Me: What? Why?

Monroe: Because if we had good grades, they thought we were a Green Bowler. [he says nonchalantly]

Me: [now stopped mid bite of the salad] What was a Green Bowler?

Bob explained that the Green Bowlers was a secret society of a group of midshipmen going back to the early 20th century that worked together to advanced themselves at the Academy and promised to do so to create as many admirals as possible. They had a house or apartment in Annapolis where they met, and a green bowl was at the door. Members would put a slip of paper in the bowl with recommendations for new members.

I had taught at that time at the Academy for nearly twenty years with a dozen years as director of the museum and I had never heard of this secret society but thought it worth some investigation. There is much more to the story that I am saving for a chapter on a new book I’m working on but here is a summary.

Another source I read said the green bowl “occupied the old mantlepiece in their first club-room on the second floor of the old part of Carvel Hall. Some members had a small bowl engraved inside their Naval Academy class rings.”

One account also mentioned a local Annapolis jeweler that provided green watch fobs for members. When I searched the museum’s database of 60,000+ artifacts for “watch fob,” there it was. Someone had donated their father’s Green Bowl watch fob and, with it, a donation letter for provenance and history.

In 1947 Captain John Crommelin testified during a House hearing that a forty-year old secret society stemming from the Academy to provide special consideration for advancement and that these “cliques” ought to be investigated. Crommelin had known about it by the time he was the executive officer on USS Enterprise during World War II when he confronted Green Bowlers air officer Commander Tom Hamilton and group commander Bucky Lee. Hamilton had played football for Navy, had been the team coach, and in 1948 became the Athletic Director.

In a private report to a congressman, Crommelin wrote that “so powerful has this organization become that certain assignments to duty are now referred to as "Green Bowler Jobs….they served prominently in the Bureau of Naval Personnel, but, they also consider it essential to the welfare of the nation that Green Bowlers serve as aides to the Secretary of the Navy and his civilian assistants.”

Although no Green Bowler had become CNO, many who benefited from Green Bowler detailers were in key positions as aides to Secretaries of the Navy and senior flag officers: O.B. Hardison to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Artemus Gates, Forrestal to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Bard, Perry to Secretary Knox, Taylor to Secretary Forrestal.”

As a result of an official congressional request, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, at this time the Chief of Naval Operations who did not believe in the conspiracy, ordered his Vice Chief Dewitt Clinton Ramsey to lead the investigation. Ramsey declined.

Nimitz: “Why?”

Ramsey: “I’m a Green Bowler”

Nimitz turned to the Deputy Chief of Naval Personnel, Admiral William Fechteler, to lead it.

Fechteler: “I’m sorry, I can’t.”

Nimitz: “Why not?”

Fechteler: “I’m a Green Bowler too.”

Nimitz then turned to his Inspector General, Admiral Leo Thebaud: “You do it.”

Thebaud shook his head and raised his hand. He was one as well.

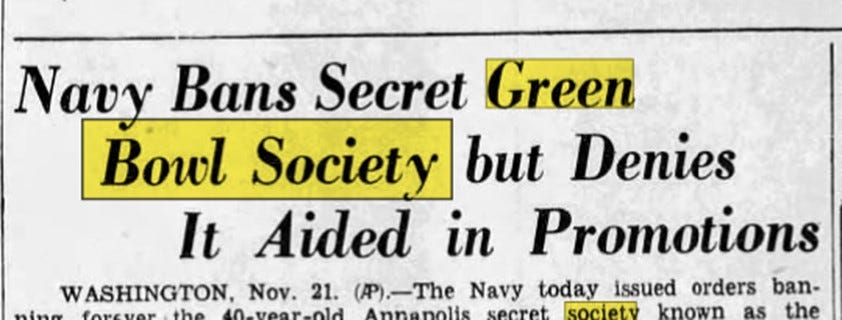

Nimitz dug deep and found Rear Admiral Frank Lowry then serving in the VCNO’s office who issued a report within a month. Newspapers across the country reported the findings but they could only rely on a press release by the navy which did not release the report itself. Lowry wrote that the Green Bowl society had any impact on promotions but the society itself was done, as directed by Nimitz, prohibiting “any secret societies among Navy men.” Lowry would write: “A coincidence or even an appearance may look evil if evil is thought, in whatever guise it is promulgated…when we are disappointed about a job assignment, leave, etc. we try to find a scapegoat on which to vent spite. The Green Bowl was just nebulous enough to serve as that goat.” Perhaps that was a stab at Crommelin.

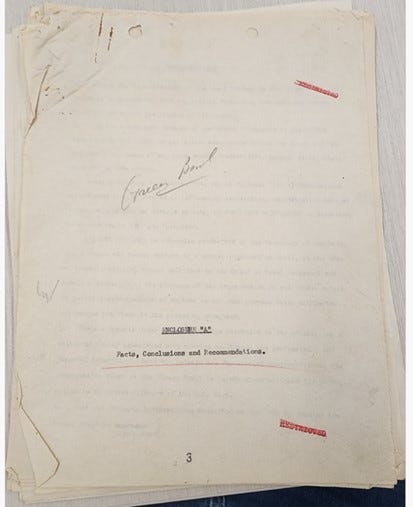

A copy of the report does not exist at the traditional repositories – the Academy, Naval War College, or National Archives. Only recently another historian and former colleague, who knew I had been working on this topic, accidentally came across the only known copy of what apparently is the Lowry report.

What really was the Green Bowl Society?

When it was formed in the early 1900s, it appears to have been an innocuous group. In a 2005 letter, the daughter of Admiral Russell Willson wrote that her father was the founder of the Green Bowl Society. He and his friends were simply looking for a place to drink beer and play cards. A few members of each subsequent class were recruited to join the organization. Willson would later serve as Chief of Staff to Fleet Admiral Ernest King during World War II. Another early member in his oral history that it was founded to “smoke, drink, talk, and amuse ourselves.”

The society’s make up began changing in the 1920s when it appears athletes, specifically football players, began to comprise it. About half of the 1924 Rose Bowl team were members. In a letter found in the Eli Vinock Papers at the Nimitz Library’s Special Collections and Archives, “The members of this ‘society’ were mostly from the USNA athletic teams…primarily football, boxing, and wrestling teams, plus the typical ‘big dealers’ in the Yard. As one reads the list with a career background in the Navy his thoughts invariably come up with ‘Now it is clear why THAT guy got so far! He wasn’t that bright or dynamic.’” The Society’s impact was felt through the 1940s. In addition to Hamilton, the former aid to Navy Secretary Forrestal, Capta E.B. Taylor, became director of athletics at the Academy. At least one Navy football loss in 1947 was blamed on the coach as a Green Bowler.

In an exchange of correspondence about the matter, author and retired Rear Admiral Kemp Tolley wrote to another retired flag officer in 1979: “Indeed I have heard of the Green Bowlers. In the beginning, I didn’t have any idea what the term meant; was it bowler hats…This must have been when I was an ensign. Then much later, probably about the time I was a two-striper, a list of members was circulated. This may have been the “inventory” taken after the death of a member, about which you wrote in your letter….Of course I was interested to see who in my class was included. One was “Rags” Parish, the other “Al” Loomis. Neither one was what you might call the conspiratorial type. Rags had a fairly routine career, nothing smashing. Al was selected for RADM (aviator) a little more than routine, but never what one might call a king ping…Thus, my feeling that the organization was a dangerous one was somewhat ameliorated.”

Indeed there was a list of Green Bowlers. Each member received a copy annually with updates. One was found among the effects of a member in 1935 who committed suicide on USS Langley. Another was found in 1942 in the desk of outgoing Commandant of Midshipmen Rear Admiral Harvey Overesch, a former football player and Green Bowler.

Was there really a conspiracy to advance?

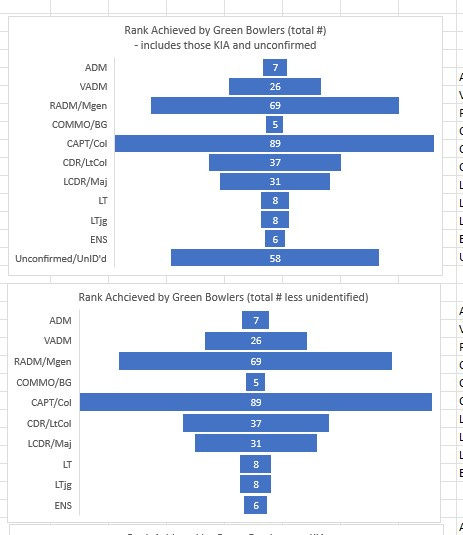

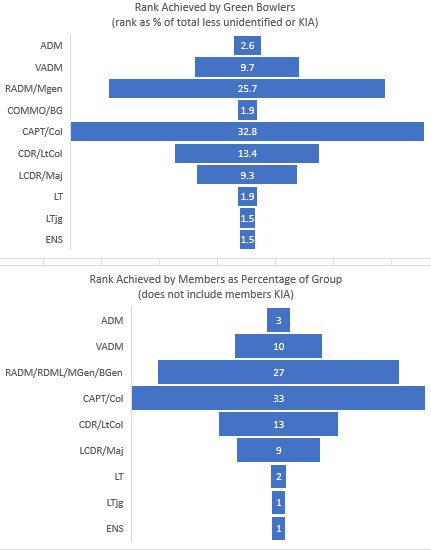

Although the Lowry report officially reported that there was no undue influence of members on promotions, it did not examine outcomes. I had the list of all the members and started tabulating the ranks they achieved as a group, among other information such as class rank, extracurricular activities, athletic teams, etc. I’ll hold off the non-Green Bowlers for now and for the next book, but the reader can make some judgements based a few of the charts below - Green Bowlers did very well in achieving higher ranks.

What of Captain John Crommelin? Although recognized as a skillful naval aviator, after he left the navy, he ran for office several times. As a segregationist, he ran for US Senate in Alabama several times, on a minor, extremist third party ticket as vice president in 1960, and later as a Democrat for president in 1968. But Crommelin had a role that impacted the early Cold War navy.

The hearing at which he testified about the Green Bowl Society was the House Committee on Expenditures regarding Unification of the Army and Navy. Two years later he became a central figure in the “Revolt of the Admirals.”

Claude, in your table of ranks achieved, does this include tombstone promotions? If so, it could account for the large number of rear admirals.